Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge

WASHINGTON (AP) — Motorists coming off the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge into Washington are treated to a postcard-perfect view of the U.S. Capitol. The bridge itself, however, is about as ugly as it gets: The steel underpinnings have thinned since the structure was built in 1950, and the span is pocked with rust and crumbling concrete.

District of Columbia officials were so worried about a catastrophic failure that they shored up the horizontal beams to prevent the bridge from falling into the Anacostia River.

And safety concerns about the Douglass bridge, which is used by more than 70,000 vehicles daily, are far from unique.

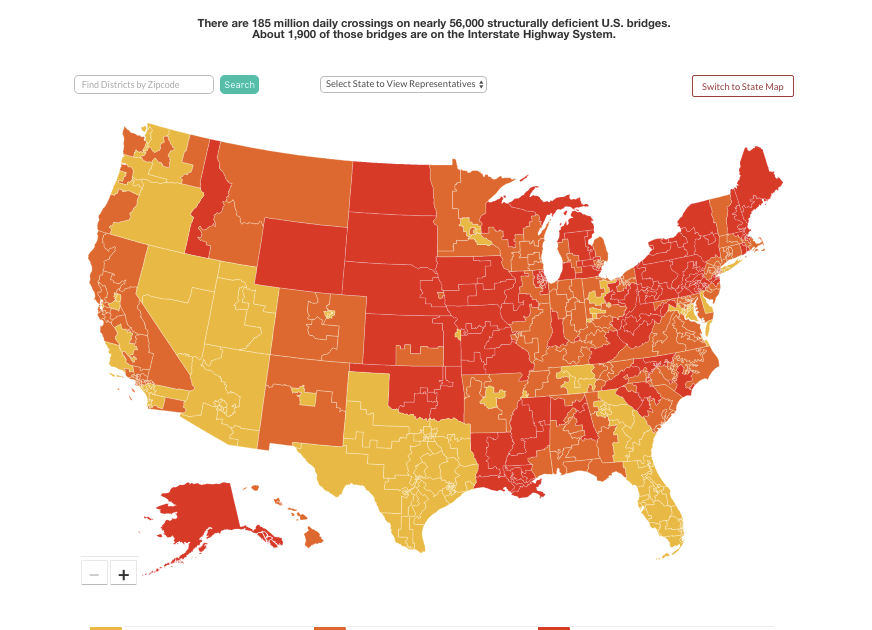

An Associated Press analysis of 607,380 bridges in the most recent federal National Bridge Inventory showed that 65,605 were classified as “structurally deficient” and 20,808 as “fracture critical.” Of those, 7,795 were both — a combination of red flags that experts say indicate significant disrepair and similar risk of collapse.

A bridge is deemed fracture critical when it doesn’t have redundant protections and is at risk of collapse if a single, vital component fails. A bridge is structurally deficient when it is in need of rehabilitation or replacement because at least one major component of the span has advanced deterioration or other problems that lead inspectors to deem its condition poor or worse.

Engineers say the bridges are safe. And despite the ominous sounding classifications, officials say that even bridges that are structurally deficient or fracture critical are not about to collapse.

The AP zeroed in on the Douglass bridge and others that fit both criteria — structurally deficient and fracture critical. Together, they carry more than 29 million drivers a day, and many were built more than 60 years ago. Those bridges are located in all 50 states, plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, and include the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, a bridge on the New Jersey highway that leads to the Lincoln Tunnel, and the Main Avenue Bridge in Cleveland.

The number of bridges nationwide that are both structurally deficient and fracture critical has been fairly constant for a number of years, experts say. But both lists fluctuate frequently, especially at the state level, since repairs can move a bridge out of the deficient categories while spans that grow more dilapidated can be put on the lists. There are occasional data-entry errors. There also is considerable lag time between when state transportation officials report data to the federal government and when updates are made to the National Bridge Inventory.

Many fracture critical bridges were erected in the 1950s to 1970s during construction of the interstate highway system because they were relatively cheap and easy to build. Now they have exceeded their designed life expectancy but are still carrying traffic — often more cars and trucks than they were originally expected to handle. The Interstate 5 bridge in Washington state that collapsed in May was fracture critical.

Cities and states would like to replace the aging and vulnerable bridges, but few have the money; nationally, it is a multibillion-dollar problem. As a result, highway engineers are juggling repairs and retrofits in an effort to stay ahead of the deterioration.

There are thousands of inspectors across the country “in the field every day to determine the safety of the nation’s bridges,” Victor Mendez, head of the Federal Highway Administration, said in a statement. “If a bridge is found to be unsafe, immediate action is taken.”

At the same time, all that is required to cause a fracture critical bridge to collapse is a single unanticipated event that damages a critical portion of the structure.

“It’s kind of like trying to predict where an earthquake is going to hit or where a tornado is going to touch down,” said Kelley Rehm, bridges program manager for the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

Signs of age are clear. The Douglass bridge, also known as the South Capitol Street Bridge, was designed to last 50 years. It’s now 13 years past that. The district’s transportation department has inserted so-called catcher beams underneath the bridge’s main horizontal beams to keep the bridge from falling into the river, should a main component fail.

Alesia Tisdall, who drove over the bridge every day for 15 years but now crosses it only occasionally, said she found its “bounce” unnerving.

“You’d look at the person sitting next to you like, ‘Did you feel that bounce?’ And they’d be looking back at you like they were thinking the same thing,” said Tisdall, a computer systems specialist at the Justice Department.

Peter Vanderzee, CEO of Lifespan Technologies of Alpharetta, Ga., which uses special sensors to monitor bridges for stress, said steel fatigue is a problem in the older bridges.

“Bridges aren’t built to last forever,” he said. He compared steel bridges to a paper clip that’s opened and bent back and forth until it breaks.

“That’s a fatigue failure,” he said. “In a bridge system, it may take millions of cycles before it breaks. But many of these bridges have seen millions of cycles of loading and unloading.”

That fatigue is evident in a steel truss bridge over Interstate 5 in Washington state — south of the similar steel truss that collapsed in May. The span that carries northbound drivers over the east fork of the Lewis River was built in 1936.

Because of age, corrosion and metal fatigue caused by vibration, the state has implemented weight restrictions on the bridge. Washington state Department of Transportation spokeswoman Heidi Sause said the bridge wasn’t built for the kind of wear — bigger loads and more traffic — that is now common.

“This is a bridge that we pay close attention to and we monitor very carefully,” Sause said.

The biggest difference between the bridge over the Lewis River and the one over the Skagit River that collapsed May 23 is that the span still standing has actually been listed in worse condition. State officials hope to replace it in the next 10 to 15 years.

While the Skagit span was not structurally deficient, the I-35W bridge that collapsed in Minneapolis in 2007 had received that designation. The bridge fell during rush hour, killing 13 people and injuring more than 100. The National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the cause of the collapse was an error by the bridge’s designers, not the deficiencies found by inspectors. A gusset plate, a fracture critical component of the bridge, was too thin.

Many of the bridges included in the AP review have sufficiency ratings — a score designed to gauge the importance of replacing the span — that are much lower than the Skagit bridge. A bridge with a score less than 50 on a 100-point scale can be eligible for federal funds to help replace the span. More than 400 bridges that are fracture critical and structurally deficient have a score of less than 10, according to the latest federal inventory.

The Brooklyn Bridge is among the worst.

There are wide gaps between states in historical bridge construction and their ongoing maintenance. While the numbers at the state level are in flux, Iowa, Nebraska, Missouri and Pennsylvania have all been listed recently in the national inventory as having more than 600 bridges both structurally deficient and fracture critical.

Pennsylvania has whittled down its backlog of structurally deficient bridges but still has many more to go, with an estimated 300 bridges in position to move onto the structurally deficient list every year if no maintenance is done. Barry Schoch, the state transportation secretary, said in an interview that officials would like to add redundancy to fracture critical bridges when they can, particularly if a bridge is also structurally deficient.

“Those are high on the priority list,” Schoch said.

After the 1983 collapse of the I-95 bridge over the Mianus River in Connecticut, the focus turned to a fracture critical bridge style known as pin-and-hanger assembly.

Pennsylvania worked over the following years to add catcher beams to its pin-and-hanger spans. That’s the case now on the George Wade Bridge that carries I-81 traffic across the Susquehanna River. More recently, crews have also been trying to move the bridge off the structurally deficient list after finding significant cracks in the piers.

Officials say northeastern states face particular challenges because the infrastructure there is older and the weather is more grueling, with dramatic and frequent freeze-thaw cycles that can put stress on roads and bridges.

Many Pennsylvania lawmakers have long sought to boost transportation funding, in part to address crumbling bridges. But this year’s proposals, including Gov. Tom Corbett’s $1.8 billion plan, stalled amid fights over details.

That’s a common issue among infrastructure managers in other states, who say they don’t have the money to replace all the bridges that need work. Instead, they continue to do patch fixes and temporary improvements.

Washington’s Douglass bridge has been rehabilitated twice. The catcher beams were added because the pin-and-hanger expansion joints that hold the bridge’s main girders in place had deteriorated to the point “we were concerned that we could have a failure, and that the failure could be catastrophic,” said Ronaldo Nicholson, the chief bridge engineer for the area.

“If the joint fails, then the beam doesn’t have anything to carry itself because there are only two beams. Therefore the bridge fails, which is why we call it fracture critical,” Nicholson said.

The bridge has a sufficiency rating of 60, an increase from the 49 rating in 2008 before some repair work was done. It remains structurally deficient because inspectors deemed the superstructure in poor condition due to “advanced structural steel section loss with holes and overhang bracket connection deficiencies,” according to an inspection report from earlier this year.

A new bridge would cost about $450 million if it was required to be able to open so large ships can travel the Anacostia, an infrequent occurrence, Nicholson said. If not, the cost could be as low as $300 million, he said.

Nicholson emphasized that if city officials feel the bridge is unsafe, they’ll prohibit trucks from crossing or close the span entirely. Inspections have been stepped up to every six months instead of the usual two-year intervals for most bridges. In the meantime, officials are trying to stretch the bridge’s life for another five years — the time they estimate it will take to build a replacement.

Congressional interest in fixing bridges rose after the 2007 collapse in Minneapolis, but efforts to add billions of extra federal dollars specifically for repair and replacement of deficient and obsolete bridges foundered. A sweeping transportation law enacted last year eliminated a dedicated bridge fund that had been around for more than three decades. State transportation officials had complained the fund’s requirements were too restrictive. Now, bridge repairs or replacements must compete with other types of highway projects for federal aid.

The new law requires states to beef up bridge inspection standards and qualifications for bridge inspectors. However, federal regulators are still drafting the new standards.

“Do we have the funding to replace 18,000 fracture critical bridges right now?” Rehm asked. “No. Would we like to? Of course.”